The Internship Must Go On

Peyton Stewart

LEARN BY DOING

EXTRACURRICULARS

- George's General, Theta Chi, Physics Club

- Peer Mentor, Wakeboarding Club

For many ambitious college students, the COVID-19 curveball resulted in the cancellation of highly anticipated travels abroad and exciting internship opportunities.

But in some cases, there also emerged secondary opportunities – a way of turning life's lemons into lemonade. For Washington College senior Peyton Stewart, it meant a late-breaking offer to work on the ATLAS experiment at CERN as a summer intern, all from the comfort and safety of home.

Dr. Suyog Shrestha, a CERN researcher who has close ties with Washington College, reached out about the highly prestigious and selective program. Every summer, they choose about 200 undergraduate students from around the world.

“We immediately thought of Peyton because of how well this research opportunity aligned with his interests; in fact he was unanimously recommended by the Physics Department,” said Karl Kehm, Associate Professor of Physics and Environmental Science and Chair of the Physics Dept. “He's a great student and because of COVID, his search for other summer positions had not been fruitful, so it all lined up favorably in the end.”

“As soon as that email came, I was all over it,” said Stewart, a Hackettstown, NJ native who plans to attend graduate school after earning his degree from Washington College next semester. “It was so great that I could do this remotely.”

“This internship is a real bright spot in the midst of this pandemic,” said Dr. Shrestha. “This is important work that must go on, and because the project is computational in nature, we found a way.”

So what does a summer internship look like when the experiment you work on is 4,000 miles away? For Stewart, it meant working fairly typical Monday-Friday work days, working around the time difference (9:00 AM in Chestertown is 3 PM at CERN), and weekly team meetings with participants from all around the globe.

It required him to work independently, stay focused, hit deadlines and overall be accountable to a team that was expecting him to provide results. He chatted with Shrestha on Skype, met with the team in Zoom and stayed in touch via detailed emails. In many ways, his summer internship mirrored the experience of the millions of working professionals who were abruptly sent home in mid-March to operate out of home offices.

As exciting as it was to land the internship, the focus of the work and the long-term impact it will have was the real win for Stewart, as he has contributed to what is believed will become one of the historical measurements in the world of physics.

In general terms, what matter is made up of and how these constituents of matter (elementary particles) interact with each other is described by an established theoretical framework, known as the Standard Model (SM) of Particle Physics. The SM also make predictions about the ‘behaviors' or properties of these elementary particles. The focus of this project – which has an entire team dedicated to it and will take years to complete – is the testing of one part the SM theory that has not yet been tested: a property of the Higgs boson, a unique and crucial particle discovered in 2012 at CERN, which resulted in Nobel prize in physics for theorists.

“Several phenomena observed in nature are not explained by the SM,” explained Shrestha. “And in the SM itself, one of the major properties of the Higgs boson – self-coupling -- is yet to be measured.”

And that is exactly what Stewart spent the summer working on.

Day to day, his work included analyzing simulated data to understand and reduce uncertainties on the Higgs boson self-coupling measurement. He would then generate plots of several different simulation programs, compare them with the standard simulation, and measure the differences. Twice over the summer, he presented his finding in ATLAS collaboration meetings dedicated to Higgs self-coupling measurement.

“Working with and learning from researchers around the world made for a really cool summer,” enthused Stewart. “I enjoyed learning the process and Dr. Shrestha made the whole experience great.”

“Peyton's work on modeling the top-quark background gave us insight into how various simulation programs model this major background, and how variations across simulation programs leads to larger uncertainties on the background,” explained Shrestha.

Because the SM explains many things, but not everything, the question that is always being asked is, are the properties of the elementary particles the same as what has been predicted?

“Weaknesses on the existing theories provide opportunities,” said Shrestha. “They can open up a whole new landscape and we as researchers are always trying to understand the unknown.” And finding that this property doesn't follow the expected pattern is a key discovery that can change how the subject is covered in textbooks.

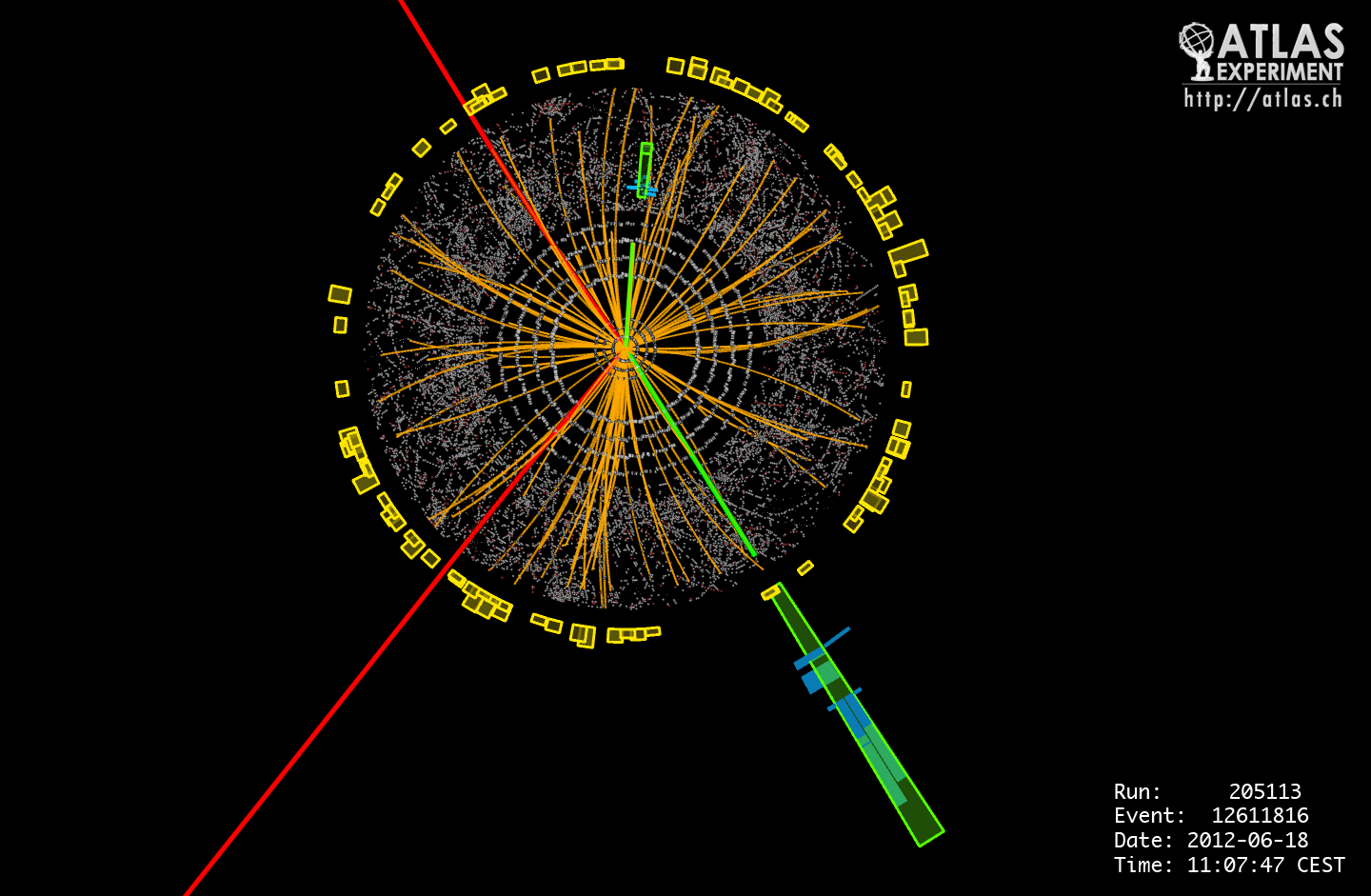

Photograph courtesy of CERN

“Hopefully Peyton's contribution will one day be part of a historic discovery,” said Shrestha. The work is in fact due to be published in 2021, meaning Stewart, as an undergrad, will be noted as having participated in an international collaboration.

Once the summer program ended, Stewart was able to continue his work through a 2-credit independent study, remotely supervised by Shrestha. Over the fall semester he has been exploring more in-depth methods to reduce the uncertainties that they have observed in various simulation programs.

Photograph courtesy of Cern

Based in Geneva, Switzerland, CERN is the European Organization for Nuclear Research, an international scientific organization established in 1954 for the purpose of collaborative search into high-energy particle physics.

In addition to making his mark in the physics world, Stewart is also busy working as a George's General, a Peer Mentor, an active member of the Theta Chi Fraternity and the Physics Club. His ultimate career goal is to earn his Ph.D. and become a professor.